One of the sectors that always fascinated me is the Dutch healthcare system. When I was a child, I wanted to become veterinarian, a job that combines both my love for animals and my desire to help people. Although that dream did not come true, I am satisfied with helping people with social innovation practises, and I have two adorable cats that I love with all my heart. Because my interest in healthcare, with or without animals included, never truly went away, in this blog I want to discuss part of my research that I did in the ambulatory care and protected living policies of the Dutch healthcare system regarding psychiatric or psychological problems. What is it, what works, and what challenges are there that need to be addressed?

Ambulatory Care & Protected Living

As the Dutch healthcare system is quite a broad topic, to clarify the subjects let’s start with defining what the terms ambulatory care and protected living mean within the context of psychiatric or psychological healthcare provided by social workers. Ambulatory care refers to healthcare that people receive in an outpatient (out of hospital) setting, such as the comfort of their own home. For example, ambulatory care is given to people who can still live on their own but need the support of a social worker to function, such as people with severe depression. Protected living concerns healthcare offered to patients in sheltered housing, who at this point in time cannot live independently. An example of those who would require protected living are people with severe autism, that cannot keep their house clean, cook healthily, or perform other daily tasks that a social worker can help them with. Organisations such as RIBW Brabant, who are financed by their local municipality, offer these services to people in need and support them on the road to recovery.

Indication Process

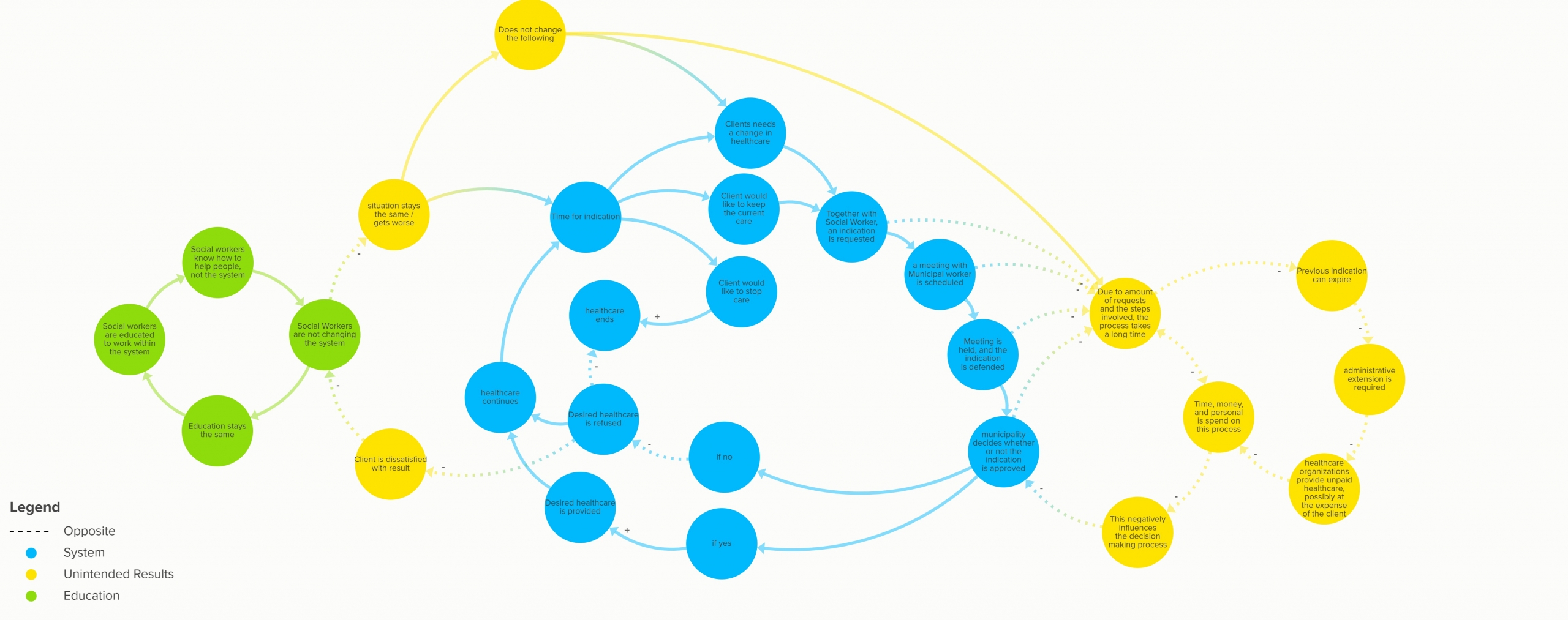

Now, let’s do a thought experiment. Imagine you are in need of either ambulatory care or protected living, how would the application process go for you? This system is visualised below in Figure 1 and starts at left blue system node ‘New Client Needs Healthcare’. First, as your healthcare will have to be reimbursed by the Wmo, the Social Support Act, you have to approach your local government. Afterwards, they will review your application, and assess if they can refer you to an organisation that can offer you the help that you need. Within 8 weeks after the application has been reviewed, if it is decided that they can offer support, you will be transferred to an organisation that fits your specific needs. An indication will be provided that specifies the type of treatment that is needed. Congratulations, you are on the road to recovery!

Figure 1: System Map – Indication Process (zoom in to see the nodes)

Let’s say that a year has passed, and unfortunately you still need the support of social workers. This means that the indication has to be renewed, so that the social workers can provide you with the care that you need. Together with the social worker, you decide if the number of hours spend on your care is sufficient, or that a change in the number of hours needs the be made. When you request a new indication, a meeting with a municipal worker is scheduled, in which you and the social worker explain and defend the number of hours the client needs. After the meeting is held, the municipal worker decides at a later point in time what the new indication will be, or if the care should stop. Then, this process repeats as often as is needed. Or at least, that is the general idea behind it…

Unintended Results

In reality, this process goes less smooth than intended. In my research I discovered that due to the number of requests and the steps involved, the indication process takes a long time. To keep this system running, quite a lot of time, money and personnel is needed. In one of my interviews with the Municipality of Breda, the employee stated that he alone was responsible for a total of 130 indications.

One of the consequences of the amount of time spend on this process, is that an indication can expire. This means that a social worker is not allowed to care for their client anymore, as the municipality has not given permission for the care. For some clients, the care that they receive will stop immediately, and they have to wait until their local municipality has decided on their new indication. Other organisations such as RIBW Brabant decide to provide healthcare anyway, regardless of the status of the current indication. However, this decision is putting RIBW Brabant at risk, because if the indication is not prolonged or the number of hours is reduced, the organisation has to pay for the provided care themselves.

Lack of Change

The first question I had upon hearing this was simple: How did this happen? Most of this can be related back to a systematic change in the Wmo in 2015. The responsibility to provide healthcare was transferred from a governmental level to a municipal level (“Het Nederlandse Zorgstelsel”, n.d.). The purpose of this decentralisation was implemented in order to be closer to the clients who are being supported by this system. However, this transfer of responsibilities was handled poorly, and unfortunately there has been no visible positive change measured by this change (“SCP”, 2020).

In this new system, there seems to be no environment of change. In one of my interviews, I talked with J. van Ginkel, a healthcare innovator and social worker. She elaborated on this environment by providing an example where she was having difficulties providing medication to her clients. This was due to a convoluted system the local pharmacy had in place at the time. She stated ‘When asking people if they are aware of this situation, everybody seems to know that this is a problem, but nobody does anything to fix it. How come so many people know that this is happening, but nobody does anything to fix it? In healthcare, it’s a lot of ‘I’m from this department’ and ‘I’m from that department’, so then they look at each other to see who is going to do something. But nobody does anything, due to the lack of a change environment.’

This perspective was confirmed by an employee of RIBW Brabant, and by a director and client manager for the WMO in Breda. They both saw the lack of innovation in the sector of Ambulatory Care and Protected Living, as well as a lack of this topic within their education. Social workers are educated to work in a system that aims to help their clients, yet not to change the system when it fails to help the clients it is meant to support.

So, now what?

The systems that are in place as of the changes in the WMO due to decentralisation of the healthcare have not been implemented properly. As there is no culture of change and innovation in the healthcare sector, the budget, time, and personnel spend on the current inefficient systems will stay in place. Although social workers do their utmost to help their clients, they do not have, nor do they take, ownership of the system that they are a part of. With this conclusion in mind, I propose that the following question needs to be tackled to change the system that is currently in place:

How might we create an environment where socials workers responsible for clients within ambulatory care or protected living conditions, take ownership and initiate change in the system they are working, which currently does not realise the needs of their clients?

A look back and a look forward

Although this subject fascinates me, I decided to focus on another challenge for my graduation project, of which you can find more information on in . I learned a lot about how to untangle complex systems when analysing the healthcare sector, but I decided to focus more on technology and education related sectors. This is because I want to develop myself further within those topics, due to my personal interest and their relation with my graduation project. Although healthcare will always interest me, I do not feel the need to develop myself further as a social innovator within this sector at this point in time.

The manner in which the Wmo was implemented showed me the importance of co-creation on a large scale. This systematic change was made for those in healthcare, but not enough with them. Perhaps if the transfer of responsibilities had been handled better, health care as it is today would be given more effectively. Alas, looking back can only bring so much value. By working on the question stated above, my hope is that everyone who is in need of ambulatory care or protected living in the Netherlands will get the support that they need.

References

Het Nederlandse Zorgstelsel. Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport. (n.d.). https://na.eventscloud.com/file_uploads/d264531c5bd30ce1e9d6d4a88ff96179_Het_Nederlandse_Zorgstelsel.pdf.

Scp: vijf jaar na nieuwe wet is zorg voor kwetsbare mensen en kinderen nog niet op orde. (2020, November 16). RTLnieuws. https://www.rtlnieuws.nl/nieuws/nederland/artikel/5196890/scp-wmo-decentralisatie-zorg-wet-maatschappelijke-ondersteuning.