“Is human nature separatism, tribalism and passionate distrust of the ‘other’? Or is it co-operation, recognition and, provided basic needs are met, a live-and-let-live attitude to all? What’s your own nature? How do you know?” (Kae Tempest)

As I kept saying throughout this journey in the other blogs, for me a more socially and environmentally just world is one in which we acknowledge our interconnectedness with the whole of life and act from that knowledge. I wish for us to understand and act upon the connection with our bodies – however they may look or abled they may be –, with other people – regardless of how far away or how different they may appear to be –, with animals, insects, trees, fungi, mountains, oceans and so on. I am continuing to discover what this means in practice, on one hand as an embodied experience and, on the other hand, as a principle of societal organisation.

What does connection feel like?

First of all, I found it valuable to understand from within myself the feeling and experience I want to cultivate in the world. What does connection feel like, I wondered?

Do you know that feeling of sharing a really good hug? – firm, but not too tight, holding each other and leaning into each other, yielding your attention for a moment just to that act of being together, to the feeling of the other. Can you recall how that feels like?

I feel it most in my belly, sometimes in my chest, sometimes all the way to my palms and fingers. It feels as a wave flushing my insides, warming and relaxing. It creates soft and comforting movement inside my body. My breath deepens. My attention expands concentrically, from within outwards, encompassing what is around me and sometimes stretching far beyond what is in sight.

How does connection feel in your body?

In their book “On Connection”, Tempest (2020) talks about this experience, too. Moreover, they do not only talk about how it feels for oneself, but about how to enable it in others through art and creativity. They speak “about how immersion in creativity can bring us closer to each other and help us cultivate greater self-awareness. About how fine-tuning the ability to feel a creative connection can help us develop our empathy and establish a deeper relationship between ourselves and the world” Tempest (2020). They proceed to elaborate on our basic need to be creative, and how “creativity encourages connection (…) to our true, uncomfortable self” Tempest (2020), which, in turn, supports us to take responsibility for our involvement and impact in the world. Tempest (2020) beautifully describes creativity as “an act of love”. Next to that, they describe connection as “the feeling of landing in the present tense” (Tempest, 2020).

The point they are making is about how creativity can facilitate connection. They highlight the multiplicity of ways that can lead to this experience, but especially focus on the role art can play in “understanding the fruit of that other place where commonality begins” (Tempest, 2020). I was touched by how aligned I found this to be with my own vision and approach. In their elaboration of their own experiences of feeling connection and of bringing that to others, I found reflections of myself. I, too, have been amazed, time and time again, by the power art has of bringing me in the right here and now, together with who and what is within and around me. Thus, as a social innovator, I wish to emancipate this power further.

The stronger and clearer the feeling of connection becomes within myself, within my own body, the more compelled and curious I am to bring it to others, too. How may I guide them through this experience? I found that engaging our own interiority and the vulnerability this entails is essential for enabling transformation. That is why the approach I am building means to support people in touching upon this level of their “true, uncomfortable self” (Tempest, 2020), in order to be able to tackle complex challenges. I find our bodies are great channels for connecting to ourselves, each other and the world around us. Thus, I have made progress in developing my own practice as a facilitator, which combines a movement approach informed by mindfulness and the performing arts, with an understanding of complexity and systems thinking.

I focus on cultivating awareness and presence within one’s internal and external world, and on employing the ability to improvise and be creative within these complex realms. Thus, my approach is to guide people into exploring the interactions between their physical sensations, emotions and thoughts, and their physical, cultural and political environment. I do this by guiding them through dance, mindfulness, reflection and dialogue. This way we tap into the pleasure of being in our bodies and the joy of movement, whether it is dancing, walking or just breathing, and co-create spaces of connection, where care, safety and trust can be cultivated.

Connected and caring communities

Furthermore, my interest in connection as a principle of societal organisation became especially focused on self-organised communities. I believe this type of practice can bring in the world the kind of feeling and experience I previously shared, and, thus, create a more just world. I learned more about self-organised communities by participating in the Vlaardingen Commons project, both as a process designer and, first and foremost, as an inhabitant. Here I felt more empowered, supported, cared for and safe than I previously have in ‘regular’, individualised ways of living. This is what I wish for myself and others to feel more of in the world.

A caring world

Upon reading ‘The Care Manifesto’ (2020), by The Care Collective, I found a vision of the world that is aligned with my own, and which supported me in strengthening my approach. They put forward the proposition of a world that prioritises care; and their concept of ‘care’ is almost synonymous with what I refer to as ‘connection’. They argue for “the nurturing of all that is necessary for the welfare and flourishing of life”, in the trust that this could create a society that is “as egalitarian, participatory and environmentally sustainable as possible” (The Care Collective, 2020) – values which I hold dearly.

They begin by highlighting the carelessness that currently defines society. They argue that “neoliberalism is uncaring by design”, for it has “profit-making as the organising principle of life” (The Care Collective, 2020), as opposed to prioritising the wellbeing of people and planet. This creates a culture that praises competitive individualism at the expense of community ties, leading to isolation and loneliness. At the same time, they showcase how the private sector is systemically favourited at the expense of the community, and how this leads to social and environmental injustices.

In turn, they come to emphasize how we are all intricately interconnected. We are shaped by our interdependencies, by “the myriad ways that our survival and our thriving are everywhere and always contingent on others” (The Care Collective, 2020), and by our concomitant need to give and receive care. I can relate to their point that the multiple crisis we are facing stem to a great degree from the denial of our interdependence and interconnection. Thus, the main point of the manifesto is that we should organise ourselves accordingly. They plead for care to become the organising principle of our society, instead of profit-making, and consequently for creating systems that enable us to care on all scales, from our own bodies to the whole planet. This means reimagining the role of states, markets and communities and creating “new caring imaginaries on a global scale” (The Care Collective, 2020).

A ‘caring state’ would, therefore, have as its primary function to cater for the caring needs (both to receive and give care) of its citizens, and for the health and wellbeing of the animate and inanimate world within its bounds – from other living beings to natural or manufactured resources and so on. Furthermore, the ‘caring state’ would focus on empowering the involvement and participation of communities and citizens, and on structurally supporting our capacities to care. As for markets, they propose a shift from overpowering capitalist markets to localised, community-based ones that benefit people and planet, instead of “the moneyed class” (The Care Collective, 2020). In this sense, they propose an alternative view of “the economy as everything that enables us to take care of each other” (The Care Collective, 2020). Most importantly, I find, is that communities – meaning the people directly involved in a certain system, whether they are inhabitants of a neighbourhood, employees of a business, students of a school and so on – would be playing a leading role. They would be at the forefront of these alternative care-based systems. We would shift our role from consumers to participants and co-creators.

“We have been encouraged to feel and act like hyper-individualised, competitive subjects who primarily look out for ourselves. But in order to really thrive we need caring communities. We need localised environments in which we can flourish: in which we can support each other and generate networks of belonging. We need conditions that enable us to act collaboratively to create communities that both support our abilities and nurture our interdependencies.” (The Care Collective, 2020)

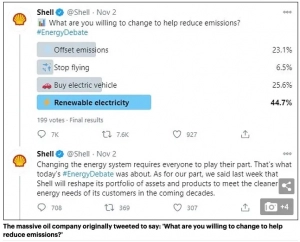

A distinction they make which I find highly relevant is that “‘caring communities’ does not mean (…) using people’s spare time to plug the caring gaps left wide open by neoliberalism. It means ending neoliberalism in order to expand people’s capacities to care” (The Care Collective, 2020). Too often the responsibility is deflected from states and markets and placed upon the shoulders of individuals. “Ordinary people should not be made feel responsible or guilty for such systemic carelessness” (The Care Collective, 2020). An example of this is Shell’s deceiving campaign which asks “what are you willing to change to help reduce emissions?”.

They place the attention and responsibility for climate breakdown on consumers, while continuing to massively invest in new overtly profitable fossil fuels projects, and deviously claiming to “meet the cleaner energy needs of its customers in the coming decades” (Shell, 2020). Instead, a just systemic transition involves all the players in the system proportionally, by equitably dividing the responsibility between those who currently do the most harm and those who are most affected. This way, it moves towards a system that mitigates for these power imbalances and mends structural injustices. Hence, a just transition, in my view, means restructuring systems so that the community can participate and take the lead, while other stakeholders – such as municipalities, businesses and so on – play a more supporting role, in contrast to the unjust and disproportionate power they currently hold.

Self-organised communities

As a student and practitioner of social innovation, I have learned that collaboration, dialogue, autonomy and flexibility are what ignite just transformation. These are more appropriate approaches for complex contexts, characterised by unpredictability and emergence. Hence, this begs the question of how we might facilitate such participatory processes – a question I have tackled in the Vlaardingen Commons project, as I previously mentioned. Through my involvement in this community as a process designer, I learned more about commons-based and participatory ways of local organisation. Additionally, I learned about how to implement and facilitate such structures. I understood how starting from a relational approach – meaning a focus on building strong interpersonal relationships –, we can create a culture of inclusion, autonomy, collaboration and adaptability. By this I mean that as the inhabitants of a neighbourhood, we take ownership of our living space and organise together to make it a fair, safe and loving environment for all those involved.

Furthermore, I saw how this culture can be a foundation for, and at the same time is stimulated by designing unique, adaptive structures. I discovered the importance of intentionally creating structures that pro-actively sustain participation, collaboration, adaptability and autonomy – vital principles for self-organised systems. Thus, I facilitated a process in which we, as a community of inhabitants, could co-create our own ways of working and organising, adapted to our unique context – socially, (sub)culturally, politically, geographically and so on. By facilitating people to discuss, create and reflect, we defined our purpose and values, we designed our own ways of dividing responsibilities and power, our own ways of taking decisions, we created space for feedback and reflection, and for tackling disagreements and conflict.

As a next step, I am intrigued by the more profound direction in which Latour, philosopher, sociologist and anthropologist, takes the idea of fair participation and representation. In his book, We Have Never Been Modern (1991), he introduces the concept of The Parliament of Things. He highlights our deep interconnection with the rest of nature and all other non-human entities around us, which we affect and are affected by through our day-to-day actions, as well as our politics. Thus, he argues for a broader political representation in decision-making processes. “Law should not be centred around Men, but around Life. We are just one party, among all animals, plants and Things.” (The Parliament of Things, 2019).

I find that this challenges current ideas of who we see as stakeholders and, thus, who we co-create with. If we are currently asking ourselves ‘who’ is part of our community, then perhaps we can expand this question to the ‘what’. The current ecological crises we find ourselves in begs us to integrate the understanding that “all life, all ecosystems on our planet are deeply intertwined” (Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature (GARN), 2018) and start acting accordingly. This vision is also very much in line with the widely encompassing concept of care that The Care Collective proposes. My own professional vision, too, is of a world where us, humans, participate actively and positively in the eco-system – within which we are so intricately connected. Thus, I wonder how this can be integrated in and elevate the practice of self-organised communities, which I am focusing on. What would our community in Vlaardingen look like, how would we be organised if we considered the non-human entities around us as community members?

CONCLUSION

In my first blog I wrote: “I want to contribute to a different story; one in which we acknowledge the interconnectedness that defines our humaneness and actively take our part in all these relationships that support life on Earth. I want to participate in creating a world that prioritizes the wellbeing of all life.” Now, at the end of this track, I would still like to contribute to a society that prioritizes connection, care and well-being in the world, and in which we organise ourselves accordingly. I have discovered more about what this abstract ideal means in practice: about what it feels like and about my way of facilitating that in the world. I learned about my passion for self-organised communities and for designing participatory processes revolving around connection and care. I strengthened my approach of facilitating by engaging the body as a medium of dialogue. As I am graduating, my next intention is to further connect to the greater movement of practitioners working on the same vision of the world. I wish to collaborate cross-disciplinarily on building communities that can sustain the complexity, ambivalence and emotional intensity of a more loving world.

References

Donovan, J. (2020). Shell faces backlash on social media after deciding to wade into the debate on climate change and how best to tackle it. Retrieved from https://royaldutchshellplc.com/2020/11/04/shell-faces-backlash-on-social-media-after-deciding-to-wade-into-the-debate-on-climate-change-and-how-best-to-tackle-it/

Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature. (2018). GARN. Retrieved from https://www.garn.org/

Tempest, K. (2020). On Connection.

The Care Collective. (2020). The Care Manifesto.

The Parliament of Things. (2019). About. Retrieved from https://theparliamentofthings.org/