In this blog I will talk about Vlaardingen Commons – a commons-based project for fairer urban housing. This is my graduation project, on which I am working right now as a process designer. It is also the place where I live, the community where I am made my home. I will mainly focus on the first role in this article – that of the process designer. However, my perspective is fundamentally formed by my involvement as a community member.

The client

Stad in de Maak (SidM)/City in the Making is a foundation that manages temporarily vacant real estate properties and turns them into spaces that contribute to the city, and “where people can live and work in a different way – affordable, sustainable” (stadindemaak, 2021). In the long term they strive to move towards permanent cooperative ownership, too. They are active in the Rotterdam area. The foundation consists of a small board of five people, amongst which three men live in the Netherlands and are most active in the projects here. Their broader vision relates to “a socially and economically sustainable life in the city, including our own basic income”. (stadindemaak, 2021) How they plan to achieve this in practice is through the following ambitions:

“1. take the property off the market

2. convert into affordable housing and workspace

3. collective ownership, collective use

4. commons free of rent

5. economical, social and ecological sustainability

6. democratically organised

7. for the large part self-organised

8. on our own terms, on our own strength” (stadindemaak, 2021)

One of the projects that SidM is working on is Vlaardingen Commons. This is an urban housing community in the Oostwijk neighbourhood of Vlaardingen. The basic principles upon which it works are “alternative forms of cohabitation, sharing facilities as much as possible and engagement with the residents of the neighbourhood” (stadindemaak, 2021). It consists of temporarily managing a neighbourhood – 2 streets comprising of 80 houses – until Samenwerking, the housing corporation who owns the houses, tears them down to build new ones.

SidM plans to create a sociocratic community with the people already living in the neighbourhood and new residents moving in. They want to experiment with self-organised, non-hierarchical, commons-based ways of organising. The purpose is to give the neighbourhood back to the people, who would manage their resources themselves. This started in May 2021 with a few vacant houses and a group of 11 new people who moved in them. I was one of them. In the following months more new people moved in and joined the project, as more houses became vacant due to more of the old residents moving out. In December 2021 the residents who already lived there and decided to stay, also joined the project and ‘officially’ became part of the Vlaardingen Commons community – at least on paper, as their contracts changed from the housing corporation to SidM.

The assignment

At the start of the project in May, SidM proposed an initial sociocratic structure in order to kickstart the community. This was composed of 4 thematic circles that people could join: program, research, maintenance, administration. As the group grew and as we lived and worked together, it became apparent that changes needed to be made to the structure. Most importantly, the community needed to create their own ways of working and organising, based on their experience, their needs, dreams and strengths. My roommate and I saw this need and came with the idea to facilitate this process. We proposed this to SidM, explaining the need that we observed. They also understood the issue and agreed to us facilitating a process to ‘restart the sociocracy’, as they said. The purpose of this would be to support the group in creating a functioning structure within the community.

It is important to facilitate this process, because people do not automatically work together in a communal, non-hierarchical way. We are all not generally used to this (sociocratic/self-organised) way of working, because our society is not currently organised by these principles. Thus, we need to take time and space to try out and learn how to do this in practice in a way that is adapted to our specific context. A bottom-up structure is fluid, adaptive and unique. It is a continuous process rather a final result. Guiding and holding this process is a substantial role to fulfil, which needs specific attention and knowledge. You can compare it to accounting – it needs a specific person to keep track of it and manage it in order to support the others to make use of it. This is the role we wish to take – “caretakers of the governance”, as the guys from SidM called it.

Our starting research question boils down to “How can we create a pro-active, self-organised community with a bottom-up, non-hierarchical structure?”. Within this, I wish to explore firstly how a self-organised community might function in practice and how might we set up such a practice – what kind of challenges we might encounter, what main elements are important, which ways of organising seem to work and so on. Secondly, I am wondering how I might facilitate such a process. How might I facilitate a group of people (a community) to create their own non-hierarchical, bottom-up structure?

Challenges and opportunities

I see numerous opportunities in this project. One of them is the fact that we have the support of SidM. This means that we can start right away, as the spatial and financial infrastructures are already in place. In comparison to this, many other community projects have a long developing time, as they need to create a team, find funding, build the houses and so on. At the same time, the downside is that it is a temporary project, that will last only for a couple of years before the housing corporation tears the houses down. In addition to this, the composition of the group represents both a challenge and an opportunity.

On one hand, some of the people chose to live here for the community, while others were ‘obliged’ to either join the community or move out. This creates discrepancies in how people engage with the project – how much they understand the concept, how much they are connected to SidM and so on. This, in turn, creates power imbalances, as some can more easily take responsibility and participate in decision-making than others. This is one of the challenges I need to take into account as a facilitator. At the same time, the large number of members (70-80 people) and diverse composition of the group – various social classes, ethnical backgrounds, ages, subcultures etc. – presents a significant opportunity. I find that the more diverse a community is, the more accurate a sample of society it is, the more relevance it has for societal transformation in general. Connecting across and beyond differences and developing compassion and care for people unlike us is crucial for an eco-entangled society.

Furthermore, as in any complex context, this project too has its paradoxes and contradictions. First of all, it aims to create a bottom-up, non-hierarchical, decentralised community. However, the idea did not come from the people already living here, but was imposed by the corporation tearing down the houses, without any consultation. The options that the residents had were accepting the project or moving out. Many of them did not have much of a choice, as they cannot afford the regular rent prices, and are living here because it is cheaper. More than this, it is under the responsibility of one small central organisation – Stad in de Maak. Officially, they have the overview and the final say over what happens here, as the new ‘managers’ of the properties.

Second of all, although it wishes to act against the housing crisis, its short-term character is a result and even a reinforcement of it. Not only does it create precarious living conditions for the more than 70 people who currently have their homes here, and do not know if they can keep their homes for more than one year before they will be displaced and will need to find another place to live in an increasingly harsher market – especially considering most of the residents here have lower than average incomes. But besides this, the new housing project that will be built will probably give way to expensive ‘properties’, following the current trend of housing development, only beneficial for profit-driven corporations.

However, neither of these paradoxes are as bad or rigid as they might seem. The fact is they can be reframed. For example, the way SidM interacts with the community is not as top-down as their formal position. And the one-year form of contract, although still very short-term, provides more security than other current temporary ways of living, such as anti-squatting, which can give as short as a two-weeks’ notice before evicting residents. In addition to this, touching upon these problems also creates the opportunity to intervene and make a change in the system.

Perspective & approach

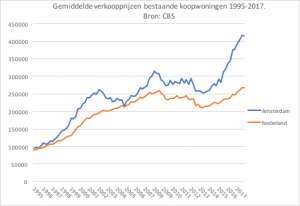

This project stems from a similar vision of the world as the one I constructed for myself: that of a more complex, regenerative, connected, safe and just one. The purpose of SidM in developing such a project is essentially contributing to a socially and economically sustainable life in the city, by creating spaces that contribute to the city and where people can live and work in affordable and sustainable ways. This comes as a response to the acute Dutch housing crisis. Buying and renting prices are becoming unaffordable in comparison to (minimum) incomes. They have risen extraordinarily in the past years, as can be seen in the graph below, showing the average buying prices in Amsterdam and the Netherlands from 1995-2017.

(destadamsterdam.nu, 2021)

This pushes people into more precarious and insecure housing situations. They often live in temporary accommodation, without a steady contract (meaning they can be kicked out with a two-weeks’ notice, for example), in properties they do not own or have much say about. Moreover, gentrification is also a serious problem, especially in bigger cities. Whole neighbourhoods are torn down, displacing inhabitants and replacing their houses with more expensive ones (Woonopstand, 2021). Especially marginalised or vulnerable people are the ones who experience the crisis the most. They are, for instance, from poorer backgrounds, of lower social class, who have adjacent mental issues or are involved in criminality. That can be seen in our neighbourhood, too. However, housing is one of the basic human needs, according to Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs. Thus, the instable housing conditions exacerbate the difficult situations some people are in.

The NOS (2021) claims that, in short, the problem is that there are not enough properties on the market. However, it is much more complex than that. The housing crisis is a systemic issue. And it has more to do with not enough affordable and accessible properties, rather than not enough physical space. Moreover, the financialization of housing is a powerful phenomenon, meaning that market forces rule the housing sector. Land and properties are primarily exploited for profit, rather than housing being treated as a right. Corporations and big investors have priority over the citizens.

Choosing profit over people seems rather dehumanizing. People seem to disregard their intrinsic connection with others, focusing on individual gain. Individualisation is a visible driver in the way the housing market functions, too. From the physical structure of most houses, to how the management of the space is organised, it facilitates separation. Thus, most inhabitants live separately from their neighbours, having little attention for getting to know each other. Landlords and housing corporations operate selfishly, prioritizing their own material gain and disregarding or even harming the wellbeing of the people they are hosting. The lack of community, of a culture of care and a spirit of sharing and mutual support create many of the problems that I previously laid out.

Therefore, this project is a concrete example of the kind of societal challenges I wish to act upon. I believe it provides a fertile ground for exploring my two layers of interest in practice – an eco-entangled view of society and an approach based on embodiment and art-based practices. In my study I feel most connected to the perspective and methods of process design. This is also the approach I wish to take for this project. I wish to facilitate the process of the group creating our own unique, fair, fluid structure. I will do that by designing various interventions, dialogues, meetings or sessions – from more informal and neighbourly, like eating, painting or hiking together – to more formal and procedural – like general meetings, brainstorms or elections.

Through these interventions I wish to connect people to themselves, each other, their environment and the world at large. I wish to stimulate collaborative interactions and to build relationships. I wish to create a safe and just atmosphere, where vulnerability is welcome and valued. I wish to aid the forming of a web of mutual care and support. Guided by this purpose, I am curios to explore how movement and art practices can be of use. Additionally, I wonder what my own way of employing these tools is. In other words, I would like to start forming my own approach of facilitating bottom-up, non-hierarchical, decentralised communities, informed by mindfulness, dance and theatre improvisation, somatic practices and so on.