Societies across the world are facing many complex and interwoven challenges—poverty, inequality, environmental degradation, demographic change, discrimination, and violence—that threaten our efforts to enable people everywhere to live a peaceful, decent, and dignified life on a healthy planet.

- Ban Ki-moon, Secretary General of the United Nations, October 2016

The today’s world getting more complex and more intertwined every second. From the actions we take in the Netherlands, we see direct consequences on a continent far away. After the turn of the century, we became more aware of the impact our daily lives might have on others.

Since then, the perception of how to deal with these challenges changed as well. It went from a liberal perspective where a market-led approach is in the centre, to a people- and planet centred approach. Meaning that every thing we do, every challenge we take upon us, should have the people- and planets interest in the back of their minds (UNRISD, 2016). The global challenges of today cannot be fixed by thinking that the market is the solution. You cannot solve an issue with the same means as the ones that created it. We, the people, need to be the solution and part of that solution is a social approach. Transformative Social Innovation can be the tool to create the changes needed.

Being a “Free Actor”

As said before, normal people are the solution regarding transformative change. To freely quote Charlie Chaplin in the Great dictator (1940); “We, the people, have the power to create happiness. We have the power to make our life free and beautiful. To make our lives a wonderful adventure. Then, let us use that power, let us all unite. Let us fight for a new world – a decent world that give men the chance to work – that will give youth a future and old age a security.”

Now the question is how might we harness our possibility for power? And where do we want to use that power to create impact? Albert Einstein allegedly said, “Problems cannot be solved by the same kind of thinking that created them.” According to his thinking, we need to find novel and emergent solutions to the challenges that we face every day.

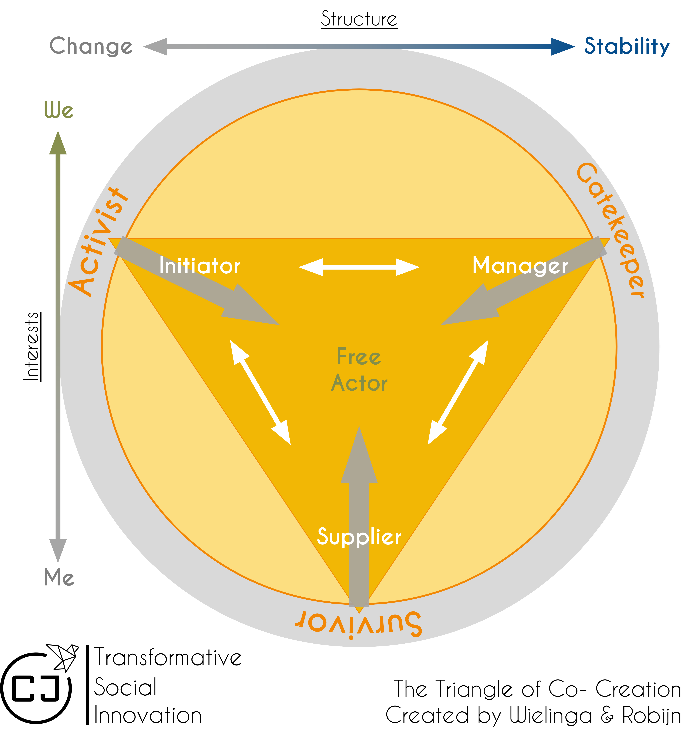

Individuals can play a role in creating new practices to challenge the complexity of today. An individual might be the person to spark the idea for change and transformation. In the Triangle of Co- Creation this person is called the “activist.” For example, an activist can put certain challenges on the agenda. However, that spark must keep on burning. That is where a free actor is needed. They can pull the Activist, who is solely looking for change, towards a centre of collaboration where co-creative actions can occur, meaning that the people who are in the possibility of change making, take that responsibility.

Wielinga & Robijn describe the free actor as the one that does whatever is required to promote the vitality of the network. They take the freedom to act, with or without mandate (2020). In a way they are the ones that create the physical and cognitive space for co-creation. This is visualized in the Triangle of Co-Creation. As shown in the visual, three roles are crucial in collaboration. However, to create true cooperation, connection is needed between the different positions. This is the main activity for the free actor. They should have the possibility to freely roam the space and link ideas & persons where needed.

Now I wonder, in the bigger picture, are there organizations within civil society who can be that free actor on a larger scale? Is it possible for a non-governmental organization to be the link between the different elements within the Triangle of Co- Creation?

Very, very short history of Bosnia & Herzegovina

As discussed in a previous blog, I have a special interest in Bosnia & Herzegovina. Since 2014 I visited the country regularly and I fell in love with the people. They are surly and reserved, yet thankful and loving. This is how I would describe the Bosnian locals. However, underneath this first impression, a great amount hidden pain, doubt and uncertainty is present.

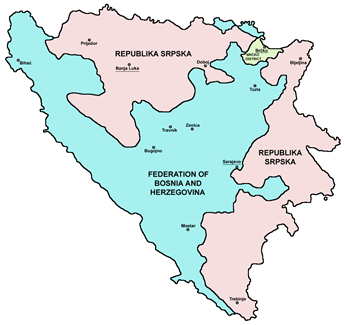

In 1991, Bosnia & Herzegovina declared themselves independent from former Yugoslavia. This triggered a civil war between three ethnicities that lasted almost four years. After an international intervention, the Dayton Peace Agreement, signed in 1995, formally ended the Bosnian War. However, the country never fully transformed past a post-conflict state to a successfully socio-economic and politically stable nation. Part of the reason that this transformation never occurred was the very same agreement that made peace possible.

The three ethnicities that fought, all received equal representation in government. While this created peace, another result was a deeply complex and decentralized system of governance. Each ethnic group has their own representation and the past shows that collaboration is hard to accomplish. This government is positioned in two ethnic entities, ten cantons, and one district. With ethnic government rhetoric that only speaks for their “own” group, the country ended up with a fragmented, ethnically divided, and under-resourced public administration sector (Kartsonaki, 2017). This leaves the government incapable of tackling current challenges such as, poverty, unemployment, an aging population, emigration social exclusion and inequality (United Nations Population Fund, 2020). As said, there is a load of hidden pain within the population of Bosnia-Herzegovina. The uncertainty and rising inequality are something that puts pressure on the country. However, there are people that want change, need change, and can create change. The challenge is to make these people heard and let them become the leaders of tomorrow.

Social Innovation in a post-conflict country

While the nation’s government refuses to create a difference, the triangle of co-creation shows that people can create change. Non-governmental organizations can play a massive role in facilitating this transformation. In the years after the war, international aid and development organizations became influential actors within Bosnia. This led to the establishment of many local NGOs. However, these local NGOs are often totally dependent on international financial aid, which means that their existence is fragile. In addition, funding from the EU is increasing towards multilateral organization, which reduces the funding for local NGOs. This leads to either the dissolvement of a local NGO or shift towards less transparent financial donors (Bozic, 2021). Also, from a TSI perspective, nation wide funding is less favourable than local support. TSI believes in a bottom-up approach where individuals get support and connections are created to build a new dominant force. We need free actors that take responsibility. So, the question is, how? And how might we support this?

A Dutch NGO can serve local NGOs or community leaders in becoming that free actor mentioned earlier. Supporting these local community leaders in creating networks, enables them to create a multitude of connections that make them, what Taleb calls, anti-fragile and assist them in their task to create co-creation. Not by replacing national institutions, but by creating bridges, understanding and common goals. I believe that this is a sustainable form of humanitarian work that might improve the lives of people all around the globe. The goal for transformative change is not set in stone. How Transformative Social Innovations (TSI) develops depends on a multitude of external factors, such as culture. However, as Ban Ki Moon explained, poverty, inequality, environmental degradation, demographic change, discrimination, and violence are intertwined in a way that makes finding solutions complex. TSI can be used to create connection that are needed to challenge these complexities. And NGOs can play their role in creating these connections.

Please reach out with any comment, complaint, or other feedback you might have.

Hvala vam na čitanju,

Jeffrey

References

Bozic, A. (2021). Social innovation in a post-conflict setting: examining external factors affecting social service NGOs. Development Studies Research, 170-180.

Chaplin, C., Chaplin, C., Goddard, P., & (Firm), F. V. (1940). The Great Dictator. United States: Charles Chaplin Film Corp.

Kartsonaki, A. (2017, March 28). Twenty Years After Dayton: Bosnia-Herzegovina (Still) Stable and Explosi. Civil Wars, pp. 488-516. doi:10.1080/13698249.2017.1297052

United Nations Population Fund. (2020). Population Situation Analysis in Bosnia and Herzegovina. SeCons. Taken from https://ba.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/psa_bih_final_november_2020_eng_0.pdf

UNRISD. (2016). Policy Innovations for Transformative Change. Switzerland: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development.

Wielinga, E., & Robijn, S. (2020). Energising Networks; Tools for co-creation. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers.